Thomas Jefferson Hotel: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

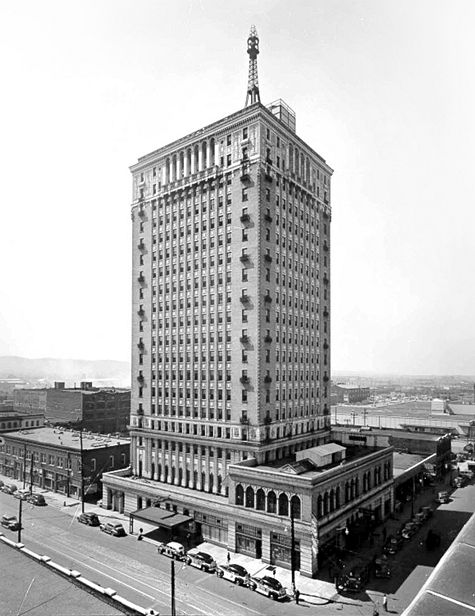

[[Image:Thomas Jefferson Hotel.jpg|right|thumb| | [[Image:Thomas Jefferson Hotel.jpg|right|thumb|475px|The Thomas Jefferson Hotel in 1949. Photo by A. C. Keily. {{BPL permission caption|http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll6,1183}}]] | ||

The '''Thomas Jefferson Hotel''' (later the '''Cabana Hotel''') is a 19-story building, formerly a | The '''Thomas Jefferson Hotel''' (later the '''Cabana Hotel''') is a 19-story building, formerly a 300-room hotel, completed in [[1929]] at 1631 [[2nd Avenue North]] on the western side of downtown [[Birmingham]]. | ||

The hotel was planned and developed by the [[Union Realty Company]], headed by [[Henry Cobb]]. The company was organized in November [[1925]] in the office of architect [[David O. Whilldin]], who prepared the design for the $1.5 million project. The Foster-Creighton Company of Nashville, Tennessee was selected as contractor and work began on the site in May [[1926]]. Progress was halted in April [[1927]] when one of the projects financiers, the Adair Realty and Trust Company of Atlanta, Georgia failed. A new holding company was formed and work resumed in July [[1928]]. Costs reached $2.5 million before it opened on [[September 7]], [[1929]]. The hotel's opening week featured nightly banquets and dances featuring an orchestra from New York. | The hotel was planned and developed by the [[Union Realty Company]], headed by [[Henry Cobb]]. The company was organized in November [[1925]] in the office of architect [[David O. Whilldin]], who prepared the design for the $1.5 million project. The Foster-Creighton Company of Nashville, Tennessee was selected as contractor and work began on the site in May [[1926]]. Progress was halted in April [[1927]] when one of the projects financiers, the Adair Realty and Trust Company of Atlanta, Georgia failed. A new holding company was formed and work resumed in July [[1928]]. Costs reached $2.5 million before it opened on [[September 7]], [[1929]]. The hotel's opening week featured nightly banquets and dances featuring an orchestra from New York. The hotel was stocked with 7,000 pieces of silverware, 5,000 glasses and 4,000 sets of linen. The luxury hotel hosted many famous guests to the city, including Mickey Rooney and Ethel Merman. During [[prohibition]], bellboys schemed to purchase confiscated liquor from police to provide to guests. | ||

The hotel featured an ornate marble lobby, a large ballroom, and a rooftop mooring mast intended for use by dirigibles. The ground floor incorporated space for six shops and the basement included a billiard room and barber shop. The ballroom and dining rooms on the second floor opened out onto roof terraces from which the main tower rose. A Corinthian colonnade in glazed white terra-cotta set off the base of the tower, with the hotel entrance marked by a metal canopy. The fourth floor created an entablature, punctuated by the rhythm of windows that continued in brick for 13 more floors. The tower was capped on the top two floors with ornamented terra-cotta, including a balustrade and arched deep-set openings. The corners of the tower were clad in white brick to provide visual supports for the upper portion of the tower, while the narrow strips of brick between the windows were tan in color, each capped with a white acanthus leaf at the top. The edge of each corner was softened with a twisted-rope moulding, rising to a sculpted satyr at the top. The cornice rests on tightly-spaced brackets with a shallow overhang of red mission tile suggesting a sloped roof. | The hotel featured an ornate marble lobby, a large ballroom, and a rooftop mooring mast intended for use by dirigibles. The ground floor incorporated space for six shops and the basement included a billiard room and barber shop. The ballroom and dining rooms on the second floor opened out onto roof terraces from which the main tower rose. A Corinthian colonnade in glazed white terra-cotta set off the base of the tower, with the hotel entrance marked by a metal canopy. The fourth floor created an entablature, punctuated by the rhythm of windows that continued in brick for 13 more floors. The tower was capped on the top two floors with ornamented terra-cotta, including a balustrade and arched deep-set openings. The corners of the tower were clad in white brick to provide visual supports for the upper portion of the tower, while the narrow strips of brick between the windows were tan in color, each capped with a white acanthus leaf at the top. The edge of each corner was softened with a twisted-rope moulding, rising to a sculpted satyr at the top. The cornice rests on tightly-spaced brackets with a shallow overhang of red mission tile suggesting a sloped roof. | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

A $35,000 improvement project was undertaken in [[1933]]. Some of the retail spaces were subsumed into a larger hotel lobby with an electric fireplace. The dining room was similarly expanded and a banquet room was constructed over part of the roof terrace. It was only the first of several renovations for numerous owners. The [[Stirrup Cup]] lounge opened at the hotel on [[October 4]], [[1940]]. [[Birmingham City Commission]]er [[Bull Connor]], having found an old city ordinance against erecting posts on sidewalks in [[1951]], ordered the removal of the hotel's marquee, which was so supported. | A $35,000 improvement project was undertaken in [[1933]]. Some of the retail spaces were subsumed into a larger hotel lobby with an electric fireplace. The dining room was similarly expanded and a banquet room was constructed over part of the roof terrace. It was only the first of several renovations for numerous owners. The [[Stirrup Cup]] lounge opened at the hotel on [[October 4]], [[1940]]. [[Birmingham City Commission]]er [[Bull Connor]], having found an old city ordinance against erecting posts on sidewalks in [[1951]], ordered the removal of the hotel's marquee, which was so supported. | ||

A large vertically-oriented painted sign for the Thomas Jefferson Hotel is still visible on the brick-clad west side of the tower. At one time the letters were outlined with neon tubes, fabricated and installed by [[Dixie Neon]]. | A large vertically-oriented painted sign for the Thomas Jefferson Hotel is still visible on the brick-clad west side of the tower. At one time the letters were outlined with neon tubes, fabricated and installed by [[Dixie Neon]]. In the early 1960s the property was put up for sale, but appraisers were pessimistic about its location, several blocks from the heart of the retail district, and also about the growing racial strife in the city. In [[1966]] the hotel underwent another major renovation, adding new carpeting, ice machines and automatic elevators. A special suite was reserved for [[Bear Bryant]] during games at [[Legion Field]]. | ||

As an affiliate of the National Hotels chain and under the management of [[Austin Frame]], the Thomas Jefferson advertised rooms from $9 to 18 a night and multi-room suites for $18 to 35. All rooms were air conditioned and provided with a private bath, radio, television and Muzak. The hotel operated a laundry and valet service and housed a coffee shop, lounge, pharmacy and barber shop. Nightly dinner dances were held in the Windsor Room. Other rooms available for events included the Terrace Ballroom, Jefferson Room, Green Room, Gold Room, Board Room and Director's Room. | |||

Facing citations under new fire, electrical and life safety codes, the Cabana Hotel closed | In [[1972]] the building was renamed the "Cabana Hotel" and a new neon sign was erected on the rooftop. The aging hotel was well past its prime, and by [[1981]] it was functioning as a $200/month apartment building with fewer than 100 residents. Facing citations under new fire, electrical and life safety codes, the Cabana Hotel was closed down on [[May 31]], [[1983]] and has been vacant ever since. In [[2002]] owners [[Sam Raines]] and [[Sammy Ceravalo]] listed the property for sale for $950,000. Architect [[Jeremy Erdreich]] estimated at the time that more than $20 million in repairs would be needed just to make it habitable. In [[2004]] [[Operation New Birmingham]] put it on their [[12 Most Wanted]] list of downtown buildings in need of renovation. | ||

In [[2005]] the Leer Corporation of Modesto, California, announced a $20 million proposal to convert the building into upscale condominiums, to be known as the [[Leer Tower]]. That proposal was delayed by a dispute over control of the building and the owner's inability to secure local financing. The property went into foreclosure in July [[2008]]. Subsequently the property has fallen further into disrepair, with the basement flooded by an [[underground river|underground stream]] and vagrants squatting in the upper floors. | In [[2005]] the Leer Corporation of Modesto, California, announced a $20 million proposal to convert the building into upscale condominiums, to be known as the [[Leer Tower]]. That proposal was delayed by a dispute over control of the building and the owner's inability to secure local financing. The company contracted with [[Hendon & Huckestein Architects]] to plan the renovations, which were to have included a rooftop swimming pool and four condominium units per floor. They installed new "Leer Tower" signage on the rooftop, which was first illuminated on [[August 30]], [[2007]]. | ||

[[Image:Hotel Thomas Jefferson lobby 2012.jpg|right|thumb|375px|View of the lobby in 2012]] | |||

The property went into foreclosure in July [[2008]]. Subsequently the property, now owned by [[James Glodt|James]] and [[Louise Glodt]], has fallen further into disrepair, with the basement flooded by an [[underground river|underground stream]] and vagrants squatting in the upper floors. On [[July 12]], [[2012]] a witness called the [[Birmingham Police Department]] to report seeing a parachutist take a leap from the roof of the building. | |||

In July [[2012]], the non-profit [[Thomas Jefferson Tower Inc.]], headed by [[UAB]] programmer [[Matthew Sheets]], was organized to raise funds to purchase and renovate the building. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

* Bryant, Joseph D. (July 7, 2002) "[http://www.bizjournals.com/birmingham/stories/2002/07/08/story4.html?page=all Glory days long gone for Thomas Jefferson Hotel]" {{BBJ}} | |||

* Shelby, Thomas Mark (2009) ''D. O. Whilldin: Alabama Architect''. Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society | * Shelby, Thomas Mark (2009) ''D. O. Whilldin: Alabama Architect''. Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society | ||

* Tomberlin, Michael (November 23, 2006) "Leer tower lists lobby, rooftop as focal points. | * Tomberlin, Michael (November 23, 2006) "Leer tower lists lobby, rooftop as focal points. {{BN}} | ||

* Tomberlin, Michael (May 5, 2009) "Old hotel crumbles as project collapses | * Tomberlin, Michael (May 5, 2009) "[http://blog.al.com/developments/2009/05/old_hotel_crumbles_as_project.html Old hotel crumbles as project collapses]" {{BN}} | ||

* Tomberlin, Michael (February 13, 2011) "Downtown dreams: Renovation slow for prominent buildings." | * Tomberlin, Michael (February 13, 2011) "Downtown dreams: Renovation slow for prominent buildings." {{BN}} | ||

* Shunnarah, Mandy (April 5, 2012) "[http://magiccitypost.com/2012/04/05/remembering-birminghams-past-leer-tower/ Remembering Birmingham’s Past: Leer Tower]" Magic City Post | * Shunnarah, Mandy (April 5, 2012) "[http://magiccitypost.com/2012/04/05/remembering-birminghams-past-leer-tower/ Remembering Birmingham’s Past: Leer Tower]" Magic City Post | ||

* Poe, Ryan (July 13, 2012) "Nonprofit wants to buy and renovate Leer Tower." {{BBJ}} | |||

* Robinson, Carol (July 13, 2012) "Mystery parachutist reportedly leaps from Birmingham's old Cabana Hotel." {{BN}} | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

* [http://www.emporis.com/building/leer-tower-birmingham-al-usa Leer Tower] on emporis.com | |||

* [http://looplink.wattsrealty.com/ll/17233888/1631-2nd-Avenue-North/ Leer Tower/Cabana Hotel/Thomas Jefferson Hotel] real estate listing at wattsrealty.com | |||

* [http://sketchup.google.com/3dwarehouse/details?mid=82bf0acabaf8a691c8c59bc53bd5954c 3-D model] of the Thomas Jefferson Hotel by Jordan Herring | * [http://sketchup.google.com/3dwarehouse/details?mid=82bf0acabaf8a691c8c59bc53bd5954c 3-D model] of the Thomas Jefferson Hotel by Jordan Herring | ||

Revision as of 11:00, 14 July 2012

The Thomas Jefferson Hotel (later the Cabana Hotel) is a 19-story building, formerly a 300-room hotel, completed in 1929 at 1631 2nd Avenue North on the western side of downtown Birmingham.

The hotel was planned and developed by the Union Realty Company, headed by Henry Cobb. The company was organized in November 1925 in the office of architect David O. Whilldin, who prepared the design for the $1.5 million project. The Foster-Creighton Company of Nashville, Tennessee was selected as contractor and work began on the site in May 1926. Progress was halted in April 1927 when one of the projects financiers, the Adair Realty and Trust Company of Atlanta, Georgia failed. A new holding company was formed and work resumed in July 1928. Costs reached $2.5 million before it opened on September 7, 1929. The hotel's opening week featured nightly banquets and dances featuring an orchestra from New York. The hotel was stocked with 7,000 pieces of silverware, 5,000 glasses and 4,000 sets of linen. The luxury hotel hosted many famous guests to the city, including Mickey Rooney and Ethel Merman. During prohibition, bellboys schemed to purchase confiscated liquor from police to provide to guests.

The hotel featured an ornate marble lobby, a large ballroom, and a rooftop mooring mast intended for use by dirigibles. The ground floor incorporated space for six shops and the basement included a billiard room and barber shop. The ballroom and dining rooms on the second floor opened out onto roof terraces from which the main tower rose. A Corinthian colonnade in glazed white terra-cotta set off the base of the tower, with the hotel entrance marked by a metal canopy. The fourth floor created an entablature, punctuated by the rhythm of windows that continued in brick for 13 more floors. The tower was capped on the top two floors with ornamented terra-cotta, including a balustrade and arched deep-set openings. The corners of the tower were clad in white brick to provide visual supports for the upper portion of the tower, while the narrow strips of brick between the windows were tan in color, each capped with a white acanthus leaf at the top. The edge of each corner was softened with a twisted-rope moulding, rising to a sculpted satyr at the top. The cornice rests on tightly-spaced brackets with a shallow overhang of red mission tile suggesting a sloped roof.

A $35,000 improvement project was undertaken in 1933. Some of the retail spaces were subsumed into a larger hotel lobby with an electric fireplace. The dining room was similarly expanded and a banquet room was constructed over part of the roof terrace. It was only the first of several renovations for numerous owners. The Stirrup Cup lounge opened at the hotel on October 4, 1940. Birmingham City Commissioner Bull Connor, having found an old city ordinance against erecting posts on sidewalks in 1951, ordered the removal of the hotel's marquee, which was so supported.

A large vertically-oriented painted sign for the Thomas Jefferson Hotel is still visible on the brick-clad west side of the tower. At one time the letters were outlined with neon tubes, fabricated and installed by Dixie Neon. In the early 1960s the property was put up for sale, but appraisers were pessimistic about its location, several blocks from the heart of the retail district, and also about the growing racial strife in the city. In 1966 the hotel underwent another major renovation, adding new carpeting, ice machines and automatic elevators. A special suite was reserved for Bear Bryant during games at Legion Field.

As an affiliate of the National Hotels chain and under the management of Austin Frame, the Thomas Jefferson advertised rooms from $9 to 18 a night and multi-room suites for $18 to 35. All rooms were air conditioned and provided with a private bath, radio, television and Muzak. The hotel operated a laundry and valet service and housed a coffee shop, lounge, pharmacy and barber shop. Nightly dinner dances were held in the Windsor Room. Other rooms available for events included the Terrace Ballroom, Jefferson Room, Green Room, Gold Room, Board Room and Director's Room.

In 1972 the building was renamed the "Cabana Hotel" and a new neon sign was erected on the rooftop. The aging hotel was well past its prime, and by 1981 it was functioning as a $200/month apartment building with fewer than 100 residents. Facing citations under new fire, electrical and life safety codes, the Cabana Hotel was closed down on May 31, 1983 and has been vacant ever since. In 2002 owners Sam Raines and Sammy Ceravalo listed the property for sale for $950,000. Architect Jeremy Erdreich estimated at the time that more than $20 million in repairs would be needed just to make it habitable. In 2004 Operation New Birmingham put it on their 12 Most Wanted list of downtown buildings in need of renovation.

In 2005 the Leer Corporation of Modesto, California, announced a $20 million proposal to convert the building into upscale condominiums, to be known as the Leer Tower. That proposal was delayed by a dispute over control of the building and the owner's inability to secure local financing. The company contracted with Hendon & Huckestein Architects to plan the renovations, which were to have included a rooftop swimming pool and four condominium units per floor. They installed new "Leer Tower" signage on the rooftop, which was first illuminated on August 30, 2007.

The property went into foreclosure in July 2008. Subsequently the property, now owned by James and Louise Glodt, has fallen further into disrepair, with the basement flooded by an underground stream and vagrants squatting in the upper floors. On July 12, 2012 a witness called the Birmingham Police Department to report seeing a parachutist take a leap from the roof of the building.

In July 2012, the non-profit Thomas Jefferson Tower Inc., headed by UAB programmer Matthew Sheets, was organized to raise funds to purchase and renovate the building.

References

- Bryant, Joseph D. (July 7, 2002) "Glory days long gone for Thomas Jefferson Hotel" Birmingham Business Journal

- Shelby, Thomas Mark (2009) D. O. Whilldin: Alabama Architect. Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society

- Tomberlin, Michael (November 23, 2006) "Leer tower lists lobby, rooftop as focal points. The Birmingham News

- Tomberlin, Michael (May 5, 2009) "Old hotel crumbles as project collapses" The Birmingham News

- Tomberlin, Michael (February 13, 2011) "Downtown dreams: Renovation slow for prominent buildings." The Birmingham News

- Shunnarah, Mandy (April 5, 2012) "Remembering Birmingham’s Past: Leer Tower" Magic City Post

- Poe, Ryan (July 13, 2012) "Nonprofit wants to buy and renovate Leer Tower." Birmingham Business Journal

- Robinson, Carol (July 13, 2012) "Mystery parachutist reportedly leaps from Birmingham's old Cabana Hotel." The Birmingham News

External links

- Leer Tower on emporis.com

- Leer Tower/Cabana Hotel/Thomas Jefferson Hotel real estate listing at wattsrealty.com

- 3-D model of the Thomas Jefferson Hotel by Jordan Herring