Caldwell Hotel: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

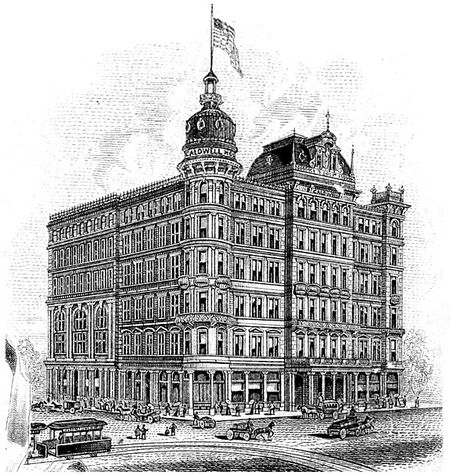

[[Image:Caldwell Hotel rendering.jpg|right|thumb|450px|Drawing of the Caldwell Hotel from an 1893 menu card]] | |||

[[Image:Caldwell Hotel rendering.jpg|right|thumb| | |||

The '''Caldwell Hotel''', completed in [[1889]], was a six-story, 100-room hotel located on the northeast corner of [[22nd Street North|22nd Street]] and [[1st Avenue North (Downtown)|1st Avenue North]] in [[downtown]] [[Birmingham]]. The hotel was destroyed in a fire on the evening of [[July 20]], [[1894]]. | The '''Caldwell Hotel''', completed in [[1889]], was a six-story, 100-room hotel located on the northeast corner of [[22nd Street North|22nd Street]] and [[1st Avenue North (Downtown)|1st Avenue North]] in [[downtown]] [[Birmingham]]. The hotel was destroyed in a fire on the evening of [[July 20]], [[1894]]. | ||

The hotel was | The idea of building a substantial hotel was proposed by [[Elyton Land Company]] president [[Henry Caldwell]] in [[1883]]. He called a special meeting of stockholders on [[December 20]] of that year to hear his plan to accomplish the venture. He proposed organizing a new '''Birmingham Hotel Company''' with $200,000 in capitol stock, which, if agreed to, could be subscribed by the Elyton Company's shareholders and paid by foregoing future dividends rather than putting up cash. As party to the transaction, [[Josiah Morris]] would secure the funds for construction in exchange for title to the land, which could then be redeemed by the new company. That scheme failed to attract enough commitments to proceed. | ||

The | On [[February 3]], [[1886]] the '''Caldwell Hotel Company''' was incorporated, with $100,000 in capital. The name was chosen to honor Henry Caldwell, who had long supported the idea of pursuing such a project, and who had agreed to allow his own residence to be moved to [[4th Avenue North]] to clear the 150-foot by 150-foot lot. | ||

Architect [[Edouard Sidel]] won a design competition judged by Caldwell and his fellow directors on [[March 28]] of that year and was instructed to proceed immediately to prepare working plans and specifications, a process he said would take about four weeks. His watercolored rendering of the hotel's main elevation was displayed to the public in the [[Alabama National Bank|Alabama State Bank]] [[Alabama National Bank Building|building]]'s [[20th Street North|20th Street]] window. | |||

Overseen by manager [[Ed Freeman]], the Caldwell | Sidel's French Renaissance revival design for a five-story building featured a central gilded dome crowning a Mansard roof topped with an allegorical figure of "Industry". The corner of the building was enriched with a circular "observatory" with its own gilded turret roof topped with a flagpole, raised 150 feet from the ground. The exterior was of pressed brick brought from Philadelphia with ornamental window caps, brackets, pilasters and other ornament in buff-colored terra cotta and white store. Wrought iron balconies graced the second, third and fourth floors. A sixth floor was added to the design during its development. | ||

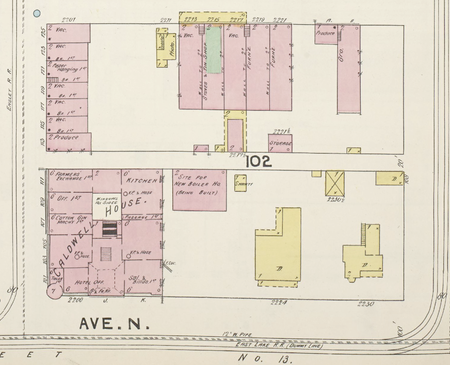

[[File:1891 Sanborn map Block 102.png|right|thumb|450px|Detail from an 1891 Sanborn Map showing the Caldwell Hotel on Block 102]] | |||

The main entrance and separate "private" and "ladies' entranceways opened into a 34- by 36-foot lobby with 18-foot ceilings. Around the lobby, overseen from the office clerk's desk, were arrayed a cloak room, passenger and freight elevators, and passages to the reading rooms, bar, billiard hall and barber shop. A 30-foot wide grand staircase, made of "Alabama iron" dominated the room. | |||

On the second floor, a 48- by 70-foot dining hall was adjoined by two parlors and a number of passenger rooms, used by those awaiting train connections and not requiring an overnight stay. The plan wrapped around a central courtyard to provide daylight to each of the hotel's 100 bed rooms. Each room was heated with steam radiators and the public areas illuminated by electric lights. | |||

[[Henry M. Allen]] was hired to oversee construction of the hotel, at a projected cost of $250,000. The company won permission from the [[City of Birmingham]], in a resolution that had to be ratified by the [[Alabama State Legislature]], to occupy a 4-foot strip of the public alley behind the building. | |||

On [[June 6]], [[1889]], before the building was completed, the company put the property up for public auction with a minimum bid of $54,849.82 in cash, representing the company's debt exclusive of bonds. The winning bidder would also be required to secure a bond to furnish the hotel and open it within three months of the date of sale, or forfeit the property at a public sale. In the event, Caldwell and [[John Boddie]] entered the sole bid, at the advertised minimum, and, in lieu of bond, assumed the company's outstanding debt of $118,000. Immediately afterward, Caldwell ordered furnishings from a company in Grand Rapids, Michigan whose agent was on-hand, and made plans to open the doors as soon as possible. | |||

When it did open in [[1889]], the hotel's 165-foot height distinguished it as Alabama's second "high-rise" building (after the Moses Building, constructed in Montgomery in [[1887]]). [[F. W. Jewell|F. W. Jewell & Co.]] leased the property and managed the business initially. Caldwell bought out Boddie's share of the hotel on [[April 29]], [[1890]]. On [[May 12]] Caldwell issued a notice that, "after the trouble with the waiters last night it had become incumbent upon the Caldwell Company to take charge of affairs." | |||

The ''[[Birmingham News]]'' reported the following week that the former manager, Jewell, had refused to give Caldwell access to the businesses books and had, in fact, removed them secretly just as he and his wife prepared to leave the city and move to Canada with numerous debts unpaid. | |||

Overseen by manager [[Ed Freeman]], the Caldwell overtook the [[Florence Hotel]] as the young city's most luxurious accommodations. The hotel's parlors and ballrooms hosted the annual balls of the [[Fortnight Club|Fortnight]], [[Monogram Club|Monogram]] and [[Cosmos Club]]s as well as numerous other meetings and events. The hotel hosted a luncheon for [[List of Presidential visits|President Benjamin Harrison]] in [[1891]]. | |||

In February [[1893]], the Caldwell served as headquarters for the [[1892 Alabama Crimson Tide football team|Alabama team]] for the [[1893 Iron Bowl|first Iron Bowl]]. A special menu prepared for the evening of [[February 22]] offered "Consomme a la Tuscaloosa" alongside "Potage a l'Auburn" as a first course before "Baked Kikoph Trout", "Braized Quarter Back of Tennessee Lamb" and other such delicacies, followed up by "One-team-out-in-the-cold Sherbet". | In February [[1893]], the Caldwell served as headquarters for the [[1892 Alabama Crimson Tide football team|Alabama team]] for the [[1893 Iron Bowl|first Iron Bowl]]. A special menu prepared for the evening of [[February 22]] offered "Consomme a la Tuscaloosa" alongside "Potage a l'Auburn" as a first course before "Baked Kikoph Trout", "Braized Quarter Back of Tennessee Lamb" and other such delicacies, followed up by "One-team-out-in-the-cold Sherbet". | ||

A year later, the Caldwell played host for the proceedings of the [[1894 Confederate Veterans Reunion]], which drew more than 10,000 visitors to the city. The two-story dining room held a massive chandelier and the lobby boasted hand-carved furnishings and fine oil paintings, as well as a marble bust of Caldwell, placed in front of a gilt Alabama coat-of-arms. A salon under the hotel's gilded dome hosted frequent high-stakes poker games. | A year later, the Caldwell played host for the proceedings of the [[1894 Confederate Veterans Reunion]], which drew more than 10,000 visitors to the city. The two-story dining room held a massive chandelier and the lobby boasted hand-carved furnishings and fine oil paintings, as well as a marble bust of Caldwell, placed in front of a gilt Alabama coat-of-arms. A salon under the hotel's gilded dome hosted frequent high-stakes poker games. | ||

Despite | Despite claims that the brick-clad building was of "fireproof construction", a [[1894 downtown fire|massive fire]] that broke out at the [[Stowers Furniture Company]] late in the evening of July 20 spread to the hotel, leaving only its brick walls standing as smoldering ruins the next morning. No lives were lost in the blaze, which was controlled during the night from spreading to the rest of the business district. | ||

Following the demise of the Caldwell, the [[Morris Hotel]], which had previously included office floors, was expanded into a full-service hotel. The ruined walls of the Caldwell remained standing until [[1905]], when the site was acquired by the [[Goodall-Brown Dry Goods Company]] for its offices and warehouse, recently renovated as the [[Goodall-Brown Lofts]]. | Following the demise of the Caldwell, the [[Morris Hotel]], which had previously included office floors, was expanded into a full-service hotel. The ruined walls of the Caldwell remained standing until [[1905]], when the site was acquired by the [[Goodall-Brown Dry Goods Company]] for its offices and warehouse, recently renovated as the [[Goodall-Brown Lofts]]. | ||

==Gallery== | |||

<gallery> | |||

File:1889 Caldwell House auction ad.png|1889 auction advertisement | |||

Image:Caldwell Hotel logo.jpg|Detail from Caldwell Hotel letterhead | |||

File:1890s 1st Ave E from 20th.jpg|View of 1st Avenue with the Caldwell in the distance | |||

Image:Caldwell Hotel after fire.jpg|The Caldwell Hotel after the July 20, 1894 fire | |||

</gallery> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

* "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/BrmnghmNP01,9923 It was sold]." (June 7, 1889) ''Daily Age-Herald'' - via | * "[https://www.newspapers.com/article/birmingham-iron-age-practicable-hotel-pr/132751150/ Practicable Hotel Project]." (November 29, 1883) ''The Iron Age'', p. 3 | ||

* "The Big Hotel Scheme" (December 13, 1883) ''The Iron Age'', p. 3 | |||

* "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/digital/collection/BrmnghmNP01/id/2038 The Caldwell House]" (April 1, 1886) ''The Weekly Iron Age'', p. 6 - via {{BPLDC}} | |||

* "The Caldwell Hotel" (May 21, 1889) ''The Evening News'', p. 1 | |||

* "Sale of the Caldwell Hotel" (May 22, 1889) ''The Evening News'', p. 3 | |||

* "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/BrmnghmNP01,9923 It was sold]." (June 7, 1889) ''Daily Age-Herald'' - via {{BPLDC}} | |||

* "Caldwell House" (May 13, 1890) {{BN}}, p. 7 | |||

* "Steals the Books Away" (May 21, 1890) {{BN}}, p. 6 | |||

* Sulzby, James F. (1960) ''Historic Alabama Hotels and Resorts''. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press | * Sulzby, James F. (1960) ''Historic Alabama Hotels and Resorts''. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press | ||

* "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1141 Grandeur settles into dust of fate, progress]" (December 19, 1971) | * "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll2,1141 Grandeur settles into dust of fate, progress]" (December 19, 1971) {{BN}} - via {{BPLDC}} | ||

* {{Laughlin-1974}} | * {{Laughlin-1974}} | ||

* McMillan, Malcolm C. (1975) ''Yesterday's Birmingham, Seeman's Historic Cities Series No. 18''. Miami: Seeman Publishing. p.54 | * McMillan, Malcolm C. (1975) ''Yesterday's Birmingham, Seeman's Historic Cities Series No. 18''. Miami: Seeman Publishing. p.54 | ||

* {{White-1977}} | * {{White-1977}} | ||

==External links== | |||

* [http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=caldwellhotel-birmingham-al-usa Caldwell Hotel] on Emporis.com, Accessed July 1, 2007. | * [http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/bu/?id=caldwellhotel-birmingham-al-usa Caldwell Hotel] on Emporis.com, Accessed July 1, 2007. | ||

[[Category:Caldwell Hotel|*]] | |||

[[Category:Former hotels]] | [[Category:Former hotels]] | ||

[[Category:1889 buildings]] | [[Category:1889 buildings]] | ||

| Line 36: | Line 66: | ||

[[Category:1894 disestablishments]] | [[Category:1894 disestablishments]] | ||

[[Category:Burned buildings]] | [[Category:Burned buildings]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:17, 1 October 2023

The Caldwell Hotel, completed in 1889, was a six-story, 100-room hotel located on the northeast corner of 22nd Street and 1st Avenue North in downtown Birmingham. The hotel was destroyed in a fire on the evening of July 20, 1894.

The idea of building a substantial hotel was proposed by Elyton Land Company president Henry Caldwell in 1883. He called a special meeting of stockholders on December 20 of that year to hear his plan to accomplish the venture. He proposed organizing a new Birmingham Hotel Company with $200,000 in capitol stock, which, if agreed to, could be subscribed by the Elyton Company's shareholders and paid by foregoing future dividends rather than putting up cash. As party to the transaction, Josiah Morris would secure the funds for construction in exchange for title to the land, which could then be redeemed by the new company. That scheme failed to attract enough commitments to proceed.

On February 3, 1886 the Caldwell Hotel Company was incorporated, with $100,000 in capital. The name was chosen to honor Henry Caldwell, who had long supported the idea of pursuing such a project, and who had agreed to allow his own residence to be moved to 4th Avenue North to clear the 150-foot by 150-foot lot.

Architect Edouard Sidel won a design competition judged by Caldwell and his fellow directors on March 28 of that year and was instructed to proceed immediately to prepare working plans and specifications, a process he said would take about four weeks. His watercolored rendering of the hotel's main elevation was displayed to the public in the Alabama State Bank building's 20th Street window.

Sidel's French Renaissance revival design for a five-story building featured a central gilded dome crowning a Mansard roof topped with an allegorical figure of "Industry". The corner of the building was enriched with a circular "observatory" with its own gilded turret roof topped with a flagpole, raised 150 feet from the ground. The exterior was of pressed brick brought from Philadelphia with ornamental window caps, brackets, pilasters and other ornament in buff-colored terra cotta and white store. Wrought iron balconies graced the second, third and fourth floors. A sixth floor was added to the design during its development.

The main entrance and separate "private" and "ladies' entranceways opened into a 34- by 36-foot lobby with 18-foot ceilings. Around the lobby, overseen from the office clerk's desk, were arrayed a cloak room, passenger and freight elevators, and passages to the reading rooms, bar, billiard hall and barber shop. A 30-foot wide grand staircase, made of "Alabama iron" dominated the room.

On the second floor, a 48- by 70-foot dining hall was adjoined by two parlors and a number of passenger rooms, used by those awaiting train connections and not requiring an overnight stay. The plan wrapped around a central courtyard to provide daylight to each of the hotel's 100 bed rooms. Each room was heated with steam radiators and the public areas illuminated by electric lights.

Henry M. Allen was hired to oversee construction of the hotel, at a projected cost of $250,000. The company won permission from the City of Birmingham, in a resolution that had to be ratified by the Alabama State Legislature, to occupy a 4-foot strip of the public alley behind the building.

On June 6, 1889, before the building was completed, the company put the property up for public auction with a minimum bid of $54,849.82 in cash, representing the company's debt exclusive of bonds. The winning bidder would also be required to secure a bond to furnish the hotel and open it within three months of the date of sale, or forfeit the property at a public sale. In the event, Caldwell and John Boddie entered the sole bid, at the advertised minimum, and, in lieu of bond, assumed the company's outstanding debt of $118,000. Immediately afterward, Caldwell ordered furnishings from a company in Grand Rapids, Michigan whose agent was on-hand, and made plans to open the doors as soon as possible.

When it did open in 1889, the hotel's 165-foot height distinguished it as Alabama's second "high-rise" building (after the Moses Building, constructed in Montgomery in 1887). F. W. Jewell & Co. leased the property and managed the business initially. Caldwell bought out Boddie's share of the hotel on April 29, 1890. On May 12 Caldwell issued a notice that, "after the trouble with the waiters last night it had become incumbent upon the Caldwell Company to take charge of affairs."

The Birmingham News reported the following week that the former manager, Jewell, had refused to give Caldwell access to the businesses books and had, in fact, removed them secretly just as he and his wife prepared to leave the city and move to Canada with numerous debts unpaid.

Overseen by manager Ed Freeman, the Caldwell overtook the Florence Hotel as the young city's most luxurious accommodations. The hotel's parlors and ballrooms hosted the annual balls of the Fortnight, Monogram and Cosmos Clubs as well as numerous other meetings and events. The hotel hosted a luncheon for President Benjamin Harrison in 1891.

In February 1893, the Caldwell served as headquarters for the Alabama team for the first Iron Bowl. A special menu prepared for the evening of February 22 offered "Consomme a la Tuscaloosa" alongside "Potage a l'Auburn" as a first course before "Baked Kikoph Trout", "Braized Quarter Back of Tennessee Lamb" and other such delicacies, followed up by "One-team-out-in-the-cold Sherbet".

A year later, the Caldwell played host for the proceedings of the 1894 Confederate Veterans Reunion, which drew more than 10,000 visitors to the city. The two-story dining room held a massive chandelier and the lobby boasted hand-carved furnishings and fine oil paintings, as well as a marble bust of Caldwell, placed in front of a gilt Alabama coat-of-arms. A salon under the hotel's gilded dome hosted frequent high-stakes poker games.

Despite claims that the brick-clad building was of "fireproof construction", a massive fire that broke out at the Stowers Furniture Company late in the evening of July 20 spread to the hotel, leaving only its brick walls standing as smoldering ruins the next morning. No lives were lost in the blaze, which was controlled during the night from spreading to the rest of the business district.

Following the demise of the Caldwell, the Morris Hotel, which had previously included office floors, was expanded into a full-service hotel. The ruined walls of the Caldwell remained standing until 1905, when the site was acquired by the Goodall-Brown Dry Goods Company for its offices and warehouse, recently renovated as the Goodall-Brown Lofts.

Gallery

References

- "Practicable Hotel Project." (November 29, 1883) The Iron Age, p. 3

- "The Big Hotel Scheme" (December 13, 1883) The Iron Age, p. 3

- "The Caldwell House" (April 1, 1886) The Weekly Iron Age, p. 6 - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "The Caldwell Hotel" (May 21, 1889) The Evening News, p. 1

- "Sale of the Caldwell Hotel" (May 22, 1889) The Evening News, p. 3

- "It was sold." (June 7, 1889) Daily Age-Herald - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- "Caldwell House" (May 13, 1890) The Birmingham News, p. 7

- "Steals the Books Away" (May 21, 1890) The Birmingham News, p. 6

- Sulzby, James F. (1960) Historic Alabama Hotels and Resorts. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press

- "Grandeur settles into dust of fate, progress" (December 19, 1971) The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Laughlin, Jerry W. (1974) Bama Burning: Fourteen Famous Fires in Alabama. self-published

- McMillan, Malcolm C. (1975) Yesterday's Birmingham, Seeman's Historic Cities Series No. 18. Miami: Seeman Publishing. p.54

- White, Marjorie Longenecker (1977) Downtown Birmingham: Architectural and Historical Walking Tour Guide. Birmingham: Birmingham Historical Society.

External links

- Caldwell Hotel on Emporis.com, Accessed July 1, 2007.