Robert Chambliss: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

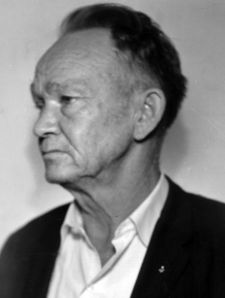

[[Image:Robert Chambliss.jpg|right|thumb|225px|Robert Chambliss' booking photo]] | [[Image:Robert Chambliss.jpg|right|thumb|225px|Robert Chambliss' booking photo]] | ||

'''Robert Edward "Dynamite Bob" Chambliss''' (born [[January 14]], [[1904]]; died [[October 29]], [[1985]]) was convicted in [[1977]] of murder for his role as co-conspirator in the [[16th Street Baptist Church]] [[1963 church bombing|bombing]] in [[1963]]. Chambliss allegedly also firebombed the houses of several black families in [[Birmingham]]. | '''Robert Edward "Dynamite Bob" Chambliss''' (born [[January 14]], [[1904]] in [[Pratt City]]; died [[October 29]], [[1985]] in [[Fairfield]]) was convicted in [[1977]] of murder for his role as co-conspirator in the [[16th Street Baptist Church]] [[1963 church bombing|bombing]] in [[1963]]. Chambliss allegedly also [[List of racially motivated bombings|firebombed]] the houses of several black families in [[Birmingham]]. | ||

Chambliss worked at the [[City of Birmingham]]'s auto repair shop in the 1940s. In May [[1949]] he threatened an African-American homebuyer not to move in, lest his house end up like [[S. L. Green]]'s, which had been [[List of racially motivated bombings|bombed]] the previous March. The threat reached the ears of [[Mayor of Birmingham|Mayor]] [[Cooper Green]] who placed Chambliss on 10-days unpaid suspension. Chambliss used his time off to loiter around the Mayor's house. | Chambliss worked at the [[City of Birmingham]]'s auto repair shop in the 1940s. In May [[1949]] he threatened an African-American homebuyer not to move in, lest his house end up like [[S. L. Green]]'s, which had been [[List of racially motivated bombings|bombed]] the previous March. The threat reached the ears of [[Mayor of Birmingham|Mayor]] [[Cooper Green]] who placed Chambliss on 10-days unpaid suspension. Chambliss used his time off to loiter around the Mayor's house. | ||

In May [[1957]] Chambliss was part of a crowd of men who attempted to blockade the entrance of the [[Birmingham Terminal Station]] against [[Integration of Birmingham Terminal Station|efforts]] by [[Fred Shuttlesworth]] to test the station's implementation of the Interstate Commerce Commission's policy of non-discrimination. The mob became violent after white activist [[Lamar Weaver]] shook Shuttlesworth's hand. | |||

Frustrated with [[Governor of Alabama|Governor]] [[George Wallace]]'s inability to slow the imposition of [[desegregation]], and also with [[Robert Shelton]]'s [[Alabama Knights of the Ku Klux Klan]], Chambliss organized a breakaway Klan group, the [[Eastview 13 Klavern]], which met at the former [[Woodlawn City Hall]] and plotted stronger terrorist actions opposing integration. | |||

==Investigation and conviction== | ==Investigation and conviction== | ||

The Federal Bureau of Investigation conducted the primary investigation of the bombing. The Bureau employed informants who were involved in the Eastview Klavern and suspected Chambliss to be involved from early on. Agents also interviewed one of Chambliss's neices, [[Petric Smith|Elizabeth Cobbs]], who reported having heard her uncle express prior knowledge of the church bombing, and to have mentioned, afterward, that it had gone off at the "wrong time" and wasn't intended to kill. | |||

Chambliss was identified, along with fellow Eastview members [[Bobby Frank Cherry]], [[Herman Frank Cash]] and [[Tommy Blanton]], as suspects in a [[May 13]], [[1965]] memo to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. At Hoover's direction, however, the Bureau closed its investigation in [[1968]] with no charges filed. Only several years later was the evidence accumulated by the Bureau revealed to state prosecutors. The records were used by Alabama attorney general Bill Baxley to reopen the case in [[1971]]. | |||

The | The case finally went to trial in [[1977]]. With crucial testimony from Cobbs, Chambliss was convicted for the murder of [[Denise McNair]] and sentenced to several terms of life imprisonment at the [[St Clair Correctional Facility]] in [[Springville]]. Still hoping that Wallace would pardon him, he maintained his innocence and rejected offers to reduce his sentence in exchange for testimony against co-conspirators. He died shortly after being transferred to [[Lloyd Noland Hospital]] for heart disease in October [[1985]]. | ||

<!--Though his remains were cremated,-->Chambliss shares a headstone with his wife, [[Flora Chambliss|Flora]] at [[Elmwood Cemetery]]. Chambliss' personal papers, including letters to his family from prison, were given to the FBI by another niece, [[Willie Mae Walker]] when it reopened prosecutions against Blanton and Cherry in the 1990s, and were deposited at the [[Birmingham Public Library Archives]] in [[2010]]. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

* "[http:// | * "Robert E. Chambliss, Figure in '63 Bombing." obituary (October 30, 1985) ''The New York Times'' | ||

* Smith, Petric J. & Elizabeth H. Cobbs (1994) ''[http://longtimecoming1963.wordpress.com/ Long Time Coming: An Insider's Story of the Birmingham Church Bombing that Rocked the World]'' Birmingham: Crane Hill Publishers, rpt. at longtimecoming1963.wordpress.com | |||

* Raines, Howell (May 21, 2000) "Alabama Presses the Klan to Answer for Its Most Heinous Bombing." ''The New York Times'' | |||

* Clary, Mike (April 14, 2001) "Birmingham's Painful Past Reopened." ''Los Angeles Times'' | * Clary, Mike (April 14, 2001) "Birmingham's Painful Past Reopened." ''Los Angeles Times'' | ||

* Sikora, Frank (2005) ''Until Justice Rolls Down: The Birmingham Church Bombing Case.'' University of Alabama Press ISBN 9780817352684. | |||

* McWhorter, Diane (November 14, 2012) "The pornography of evil." {{Weld}} | |||

* {{Thorne-2013}} | * {{Thorne-2013}} | ||

* "[http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Robert_Edward_Chambliss Robert Edward Chambliss]" (August 20, 2016) Wikipedia - accessed September 2, 2016 | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

* [http://www.bplonline.org/resources/archives/aids/AR1969.pdf Chambliss, Robert E. Papers, 1972-1987] collection guide at bplonline.org | |||

* [http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/cdm/ref/collection/p4017coll8/id/13854 State of Alabama vs. Robert E. Chambliss Trial Transcript, 1977] at bplonline.org | |||

* [http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=11212947 Robert "Dynamite Bob" Chambliss] at Findagrave.com | * [http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=11212947 Robert "Dynamite Bob" Chambliss] at Findagrave.com | ||

Latest revision as of 14:49, 13 September 2016

Robert Edward "Dynamite Bob" Chambliss (born January 14, 1904 in Pratt City; died October 29, 1985 in Fairfield) was convicted in 1977 of murder for his role as co-conspirator in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963. Chambliss allegedly also firebombed the houses of several black families in Birmingham.

Chambliss worked at the City of Birmingham's auto repair shop in the 1940s. In May 1949 he threatened an African-American homebuyer not to move in, lest his house end up like S. L. Green's, which had been bombed the previous March. The threat reached the ears of Mayor Cooper Green who placed Chambliss on 10-days unpaid suspension. Chambliss used his time off to loiter around the Mayor's house.

In May 1957 Chambliss was part of a crowd of men who attempted to blockade the entrance of the Birmingham Terminal Station against efforts by Fred Shuttlesworth to test the station's implementation of the Interstate Commerce Commission's policy of non-discrimination. The mob became violent after white activist Lamar Weaver shook Shuttlesworth's hand.

Frustrated with Governor George Wallace's inability to slow the imposition of desegregation, and also with Robert Shelton's Alabama Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, Chambliss organized a breakaway Klan group, the Eastview 13 Klavern, which met at the former Woodlawn City Hall and plotted stronger terrorist actions opposing integration.

Investigation and conviction

The Federal Bureau of Investigation conducted the primary investigation of the bombing. The Bureau employed informants who were involved in the Eastview Klavern and suspected Chambliss to be involved from early on. Agents also interviewed one of Chambliss's neices, Elizabeth Cobbs, who reported having heard her uncle express prior knowledge of the church bombing, and to have mentioned, afterward, that it had gone off at the "wrong time" and wasn't intended to kill.

Chambliss was identified, along with fellow Eastview members Bobby Frank Cherry, Herman Frank Cash and Tommy Blanton, as suspects in a May 13, 1965 memo to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. At Hoover's direction, however, the Bureau closed its investigation in 1968 with no charges filed. Only several years later was the evidence accumulated by the Bureau revealed to state prosecutors. The records were used by Alabama attorney general Bill Baxley to reopen the case in 1971.

The case finally went to trial in 1977. With crucial testimony from Cobbs, Chambliss was convicted for the murder of Denise McNair and sentenced to several terms of life imprisonment at the St Clair Correctional Facility in Springville. Still hoping that Wallace would pardon him, he maintained his innocence and rejected offers to reduce his sentence in exchange for testimony against co-conspirators. He died shortly after being transferred to Lloyd Noland Hospital for heart disease in October 1985.

Chambliss shares a headstone with his wife, Flora at Elmwood Cemetery. Chambliss' personal papers, including letters to his family from prison, were given to the FBI by another niece, Willie Mae Walker when it reopened prosecutions against Blanton and Cherry in the 1990s, and were deposited at the Birmingham Public Library Archives in 2010.

References

- "Robert E. Chambliss, Figure in '63 Bombing." obituary (October 30, 1985) The New York Times

- Smith, Petric J. & Elizabeth H. Cobbs (1994) Long Time Coming: An Insider's Story of the Birmingham Church Bombing that Rocked the World Birmingham: Crane Hill Publishers, rpt. at longtimecoming1963.wordpress.com

- Raines, Howell (May 21, 2000) "Alabama Presses the Klan to Answer for Its Most Heinous Bombing." The New York Times

- Clary, Mike (April 14, 2001) "Birmingham's Painful Past Reopened." Los Angeles Times

- Sikora, Frank (2005) Until Justice Rolls Down: The Birmingham Church Bombing Case. University of Alabama Press ISBN 9780817352684.

- McWhorter, Diane (November 14, 2012) "The pornography of evil." Weld for Birmingham

- Thorne, T. K. (2013) Last Chance for Justice: How Relentless Investigators Uncovered New Evidence Convicting the Birmingham Church Bombers. Chicago: Chicago Review Press ISBN 1613748671

- "Robert Edward Chambliss" (August 20, 2016) Wikipedia - accessed September 2, 2016

External links

- Chambliss, Robert E. Papers, 1972-1987 collection guide at bplonline.org

- State of Alabama vs. Robert E. Chambliss Trial Transcript, 1977 at bplonline.org

- Robert "Dynamite Bob" Chambliss at Findagrave.com