Wallace Rayfield: Difference between revisions

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

* "Wallace Rayfield." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 18 Mar 2006, 03:54 UTC. 22 Mar 2006, 18:58 [http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wallace_Rayfield&oldid=44308536]. | * "Wallace Rayfield." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 18 Mar 2006, 03:54 UTC. 22 Mar 2006, 18:58 [http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Wallace_Rayfield&oldid=44308536]. | ||

* Dozier, Richard; Bill Springer and Allen R. Durough (February 12, 2009) "Wallace Rayfield" panel presentation. "Collective Perspectives" series. Vulcan Park and Museum. | * Dozier, Richard; Bill Springer and Allen R. Durough (February 12, 2009) "Wallace Rayfield" panel presentation. "Collective Perspectives" series. Vulcan Park and Museum. | ||

* Boyd, Ashley (January 31, 2010) "Work of Tuscaloosa's first black architect shines in churches." ''Tuscaloosa News'' | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 15:44, 2 February 2010

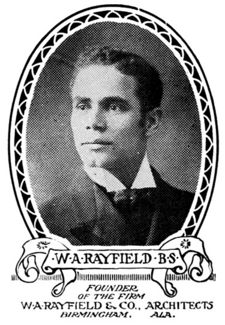

Wallace Augustus Rayfield (born May 10 or 11, 1872 (or 1873 or 1874) — died February 28, 1941) was the second formally educated practicing African American architect in the United States. He designed numerous notable structures in Birmingham and extended his practice across the United States and overseas through the sale of mail order plans and plan books.

Early life and career

Rayfield's father was a railroad porter and high school teacher, and his mother a graduate of Atlanta University. He grew up in Macon, Georgia and attended the Lewis School there, taking particular interest in a course on cartography. He went on to study at the Ballard Normal School, where his father taught, before moving to Washington D. C. to live with an aunt after his mother died.

Rayfield continued his studies at the preparatory school for Howard University. While there, he befriended Miss I. I. Mussey, daughter of the attorney representing the noted architectural office of A. B. Mullett and Company. Through that connection Rayfield secured a position with the firm where over two years he gained both practical experience and a strong desire to pursue a career in architecture.

After graduating from Howard in 1896, Rayfield moved to Brooklyn, New York to study at the Pratt Polytechnic Institute. He received his certificate from that program in 1898 and then continued his studies for one year at Columbia University, earning his bachelor of architecture in 1899.

While still a student at Columbia, Rayfield was recruited by Booker T. Washington to direct the Architectural and Mechanical Drawing Department at his Tuskegee Industrial and Normal Institute in Macon County. He began in the Fall of 1899 directing courses in mechanical and architectural drawing. Over ten years at Tuskegee he raised the program from a modest instruction in drafting to a well-respected course of architectural study. Many African-American architects began their studies at Tuskegee.

Complaining of low pay, but perhaps motivated by the treatment given to colleague Wallace Pittman, Rayfield resigned from the Institute in 1907 and opened a professional office in Birmingham. Before leaving Tuskegee he had already launched a business marketing mail-order plans nationwide. He advertised "branch offices" in Birmingham, Montgomery, Mobile, Talladega, Atlanta, Savannah, and Augusta. In the same year he married his first wife, Jennie Hutchins, a Tuskegee student from Clarksville, Tennessee.

Birmingham

Rayfield left Tuskegee Institute and moved to Birmingham in 1908 to focus on his young practice. He brought with him glowing letters of recommendation from Washington and secured a $40 commission on his first day in the city. He appeared in the city directory of that year at his residence at 109 Corrilla Street (now Center Place South). Later that year he constructed his own residence at 105 1st Avenue South in Titusville. The house was designed, financed and constructed entirely within the African American community (one of only 10 such houses in Birmingham, according to historian Phillip W. Holland). The home featured a large stained glass window and a special "architectural room" surrounded by windows in the attic level. Mr & Mrs Rayfield raised a daughter, Edith there, attending Saint Mark's Episcopal Church. Mrs Rayfield died in 1929 and was interred at Grace Hill Cemetery.

During the Depression it was impossible to keep ahead of business. On March 1, 1932 he married widow Bessie Fulwood Rogers, who was herself employed by Dr Edmund Rucker, Jr. Rayfield resided with her at 328 Iota Avenue, a few blocks from his former home. Rayfield was the leader of the group of prominent Black citizens that founded the South Elyton Civic League for the improvement of the Titusville community.

In his later years, Rayfield joined the Immaculate Conception Catholic Church on 6th Avenue South. He suffered declining health and passed away at home at the end of February 1941. He is interred at Greenwood Cemetery in Woodlawn.

Professional career

In addition to his personal office at home, Rayfield owned a series of downtown offices. The City Directory lists these as: 1717 1/2 3rd Avenue North, 402 & 404 1/2 15th Street North, the Alabama Penny Savings Bank Building (the Pythian Temple Building after 1917), and the Masonic Temple Building. According to his correspondence, he also kept offices in the Echols Building In 1913 he was listed in partnership with Alphonso Reveron. He taught one year at Industrial High School in 1919-20.

Rayfield received most of his commissions from churches. In 1909 he won a competition to serve a four-year term as official architect of the national African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was later elected Superintending Architect for the Freedmen’s Aid Society, headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio. He also completed several residences in Birmingham and a number of school buildings. It is estimated that between his professional and mail-order architectural services, that he was responsible for designing thousands of structures across the United States.

Printing plates

A collection of over 400 printing plates, including illustrations and frontispieces for books, advertisements, and other materials was found in 1993 in a barn in McCalla owned by minister Allen Durough. Durough has made it his mission to compile all the information he can about the architect who went all but unknown for most of the last century. He is the author of a book about Rayfield which will be published by the University of Alabama Press in 2010.

Notable works

Birmingham

- Edward Brown residence, 1907

- Arthur Brown residence, 1907

- A. H. Parker residence, 1907

- Wallace Rayfield residence, 1908

- 6th Avenue Baptist Church, 1910

- Thomas School, 1910

- 16th Street Baptist Church, 1911

- Windham Building, 1912

- Pythian Temple, 1913

- R. A. Blount residence, 1914

- 32nd Street Baptist Church, 1924

- J. S. Jackson residence, 1925

- 1st Congregational Church

- Harmony Street Baptist Church

- Mount Ararat Baptist Church, Ensley

- Sardis Baptist Church

- South Elyton Baptist Church

- Stewart Hall, Miles College

- Trinity Baptist Church, Smithfield

- R. T. Brown residence

- Madame Clisby residence ("The Gables")

- J. M. Coar residence

- John W. Commons residence

- A. G. Dobbins residence

- R. E. Pharrow residence

- Dunbar Hotel

- Elk's Rest

- Harriet Strong Undertaking Company building

- Indian Herb Drug Company building

- Hill Top (Smith-Gaston Residence), Fairfield

- Charles T. Mabry residence

- Metropolitan A.M.E. Zion Church

- O. K. French Cleaners Building

- R. W. Seymour residence

- T. S. Strawbridge residence

- Walton's Cafe

Tuscaloosa

- Hunter Chapel AME Zion Church

- Weeping Mary Baptist Church

- Bailey's Tabernacle Baptist Church

- St Paul AME Church

Elsewhere

- Ebenezer Baptist Church, Chicago, Illinois

- Haven Institute Dormitory, Meridian, Mississippi

- Independent Benevolent Order Home Office Building, Atlanta, Georgia

- Marlinton Methodist Church, Marlinton, West Virginia

- Marlinton Presbyterian Church, Marlinton, West Virginia

- Morning Star Baptist Church, Demopolis, Alabama

- Mount Pilgrim Baptist Church, Milton, Florida

- Mount Zion Baptist Church, Pensacola, Florida

- Public school, Paco, Texas

- St Paul's Episcopal Church, Batesville, Arkansas

- Trinity Building, South Africa

References

- Hamilton, G. P. (1911) "W. A. Rayfield, B. S., Birmingham, Ala." in Beacon Lights of the Race. Memphis, E. H. Clarke & Brother, pp. 451-7

- Brown, Charles A. (1972) W. A. Rayfield: Pioneer Black Architect of Birmingham, Ala. Birmingham: Gray Printing Company

- McKenzie, Vinson. (Fall 1993) "A Pioneering African-American Architect in Alabama: Wallace A. Rayfield, 1874-1941." Journal of the Interfaith Forum on Religion, Art & Architecture. Vol. 13

- "Wallace Rayfield." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 18 Mar 2006, 03:54 UTC. 22 Mar 2006, 18:58 [1].

- Dozier, Richard; Bill Springer and Allen R. Durough (February 12, 2009) "Wallace Rayfield" panel presentation. "Collective Perspectives" series. Vulcan Park and Museum.

- Boyd, Ashley (January 31, 2010) "Work of Tuscaloosa's first black architect shines in churches." Tuscaloosa News

External links

- Wallace A. Rayfield site by Allen R. Durough

- Rayfield Legacy project to convert 32nd St. Baptist Church in Birmingham to condominiums. Includes history of the church.