Birmingham Central Library: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

The '''Birmingham Central Library''', completed in [[1984]], is the primary location for the [[Birmingham Public Library]]. It is connected to the former main library building, now called the [[Linn-Henley Research Library]], by an elevated crosswalk over [[21st Street North|Richard Arrington, Jr Boulevard North]]. It occupies half of the small block between [[Park Place]] and [[7th Avenue North]] with a fenced surface parking lot on the [[22nd Street North|22nd Street]] side of the block. | The '''Birmingham Central Library''', completed in [[1984]], is the primary location for the [[Birmingham Public Library]]. It is connected to the former main library building, now called the [[Linn-Henley Research Library]], by an elevated crosswalk over [[21st Street North|Richard Arrington, Jr Boulevard North]]. It occupies half of the small block between [[Park Place]] and [[7th Avenue North]] with a fenced surface parking lot on the [[22nd Street North|22nd Street]] side of the block. | ||

A [[1977]] bond issue provided approximately $ | A [[1977]] bond issue provided approximately $8.5 million for construction of a new central library. The site of the long-demolished [[Jefferson County Courthouse]] on the east side of [[21st Street North|21st Street]] between [[3rd Avenue North|3rd]] and [[4th Avenue North]] was selected through a process of "lengthy studies and public hearings" and the city negotiated its purchase for $1.5 million. By [[1979]] it was thought that the project could cost as much as $20 million and another $9 million was included in a second bond referendum on [[June 26]]. [[David Herring]], chair of the [[Birmingham City Council]]'s finance committee, said that if the second referendum failed he would recommend canceling the library project. | ||

Ultimately the board to | In May [[1979]] city planning consultants [[Angelos Demetriou]] and [[Pedro Costa]] recommended another site on [[6th Avenue North]]. They argued that by building the library on the western side of town, that it could serve as a catalyst for redevelopment in the area, and in particular for new housing. The property they recommended, which later became the home of the [[Birmingham Civil Rights Institute]] was owned by [[A. G. Gaston]], who promised that he would be willing to sell the property for whatever it appraised for, even if he had to take a loss. The anticipated appraisal value would have been in the range of $950,000. | ||

Mayor [[David Vann]] countered that evaluating the new site and negotiating its acquisition could delay the project by up to 18 months, at considerable cost, and also would entail demolition of the [[Gaston Motel]], which was already remembered as a major [[Civil Rights Movement]] site. Vann did say that he was interested in seeking a major public investment for that area, and spoke with Governor [[Fob James]]' office about the possibility of constructing a new state office building there. In any case, he agreed to abide by the decision of the City Council on the selection of a site. The June 26 referendum was defeated, but the city and library board elected to proceed with the project. In [[1980]] another alternative site was considered as the board worked with Morris/Aubrey of Houston, Texas to look at the possibility of purchasing and renovating the [[Loveman's building|downtown flagship store]] of the [[Loveman's]] chain, which had just announced its closing. | |||

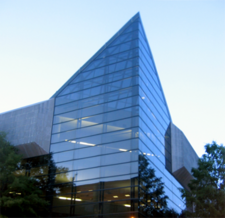

Ultimately all the previously-considered sites were rejected and the board decided to construct its new building across 21st Street from the existing library, and to connect them with an elevated crosswalk. Morris/Aubrey partnered with [[KPS Group, Inc.]] to design the crisply modern structure. It features a multi-story atrium piercing the roof and jutting into the sky on the southwest corner. Another central skylight illuminates a bank of escalators from the ground floor to the fourth floor gallery and offices. The exterior is clad in Indiana limestone to match its older sibling. The [[Champion Construction Company]] was the general contractor. A grand opening celebration was held on [[September 15]]-[[September 16|16]], [[1984]] with a parade that featured giant puppets, a dragon, marching bands, the [[Birmingham Stallions]] cheerleaders, Wally "Famous" Amos, and costumed children. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

* Shook, Phil H. (April 3, 1980) "[http://www.birminghamrewound.com/features/farewell_lovemans.htm The Loveman's years: Curtain closing on lifetime of memories]" | * Northrop, John (May 25, 1979) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/cdm/ref/collection/p4017coll2/id/1090 Gaston willing 'to take a loss' on proposed site for library]" {{BPH}} - via [[Birmingham Public Library]] Digital Collections | ||

* Friedman, Richard (May 25, 1979) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/cdm/ref/collection/p4017coll2/id/1049 Vann wants library built next to church." {{BN}} - via [[Birmingham Public Library]] Digital Collections | |||

* Shook, Phil H. (April 3, 1980) "[http://www.birminghamrewound.com/features/farewell_lovemans.htm The Loveman's years: Curtain closing on lifetime of memories]" {{BN}}- via Birmingham Rewound | |||

* Sides, Rochelle (September 1984) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll8,4196 Celebrating the Past, Reflecting the Future]" ''Birmingham Artline''. Vol. 1, No. 6 | * Sides, Rochelle (September 1984) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/u?/p4017coll8,4196 Celebrating the Past, Reflecting the Future]" ''Birmingham Artline''. Vol. 1, No. 6 | ||

Revision as of 23:06, 20 June 2014

The Birmingham Central Library, completed in 1984, is the primary location for the Birmingham Public Library. It is connected to the former main library building, now called the Linn-Henley Research Library, by an elevated crosswalk over Richard Arrington, Jr Boulevard North. It occupies half of the small block between Park Place and 7th Avenue North with a fenced surface parking lot on the 22nd Street side of the block.

A 1977 bond issue provided approximately $8.5 million for construction of a new central library. The site of the long-demolished Jefferson County Courthouse on the east side of 21st Street between 3rd and 4th Avenue North was selected through a process of "lengthy studies and public hearings" and the city negotiated its purchase for $1.5 million. By 1979 it was thought that the project could cost as much as $20 million and another $9 million was included in a second bond referendum on June 26. David Herring, chair of the Birmingham City Council's finance committee, said that if the second referendum failed he would recommend canceling the library project.

In May 1979 city planning consultants Angelos Demetriou and Pedro Costa recommended another site on 6th Avenue North. They argued that by building the library on the western side of town, that it could serve as a catalyst for redevelopment in the area, and in particular for new housing. The property they recommended, which later became the home of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute was owned by A. G. Gaston, who promised that he would be willing to sell the property for whatever it appraised for, even if he had to take a loss. The anticipated appraisal value would have been in the range of $950,000.

Mayor David Vann countered that evaluating the new site and negotiating its acquisition could delay the project by up to 18 months, at considerable cost, and also would entail demolition of the Gaston Motel, which was already remembered as a major Civil Rights Movement site. Vann did say that he was interested in seeking a major public investment for that area, and spoke with Governor Fob James' office about the possibility of constructing a new state office building there. In any case, he agreed to abide by the decision of the City Council on the selection of a site. The June 26 referendum was defeated, but the city and library board elected to proceed with the project. In 1980 another alternative site was considered as the board worked with Morris/Aubrey of Houston, Texas to look at the possibility of purchasing and renovating the downtown flagship store of the Loveman's chain, which had just announced its closing.

Ultimately all the previously-considered sites were rejected and the board decided to construct its new building across 21st Street from the existing library, and to connect them with an elevated crosswalk. Morris/Aubrey partnered with KPS Group, Inc. to design the crisply modern structure. It features a multi-story atrium piercing the roof and jutting into the sky on the southwest corner. Another central skylight illuminates a bank of escalators from the ground floor to the fourth floor gallery and offices. The exterior is clad in Indiana limestone to match its older sibling. The Champion Construction Company was the general contractor. A grand opening celebration was held on September 15-16, 1984 with a parade that featured giant puppets, a dragon, marching bands, the Birmingham Stallions cheerleaders, Wally "Famous" Amos, and costumed children.

References

- Northrop, John (May 25, 1979) "Gaston willing 'to take a loss' on proposed site for library" Birmingham Post-Herald - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Friedman, Richard (May 25, 1979) "[http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/cdm/ref/collection/p4017coll2/id/1049 Vann wants library built next to church." The Birmingham News - via Birmingham Public Library Digital Collections

- Shook, Phil H. (April 3, 1980) "The Loveman's years: Curtain closing on lifetime of memories" The Birmingham News- via Birmingham Rewound

- Sides, Rochelle (September 1984) "Celebrating the Past, Reflecting the Future" Birmingham Artline. Vol. 1, No. 6

External links

- Birmingham Public Library website